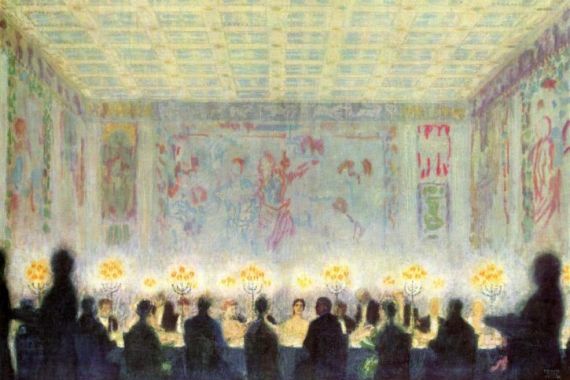

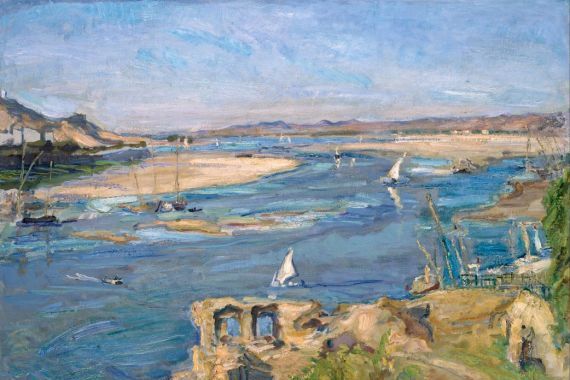

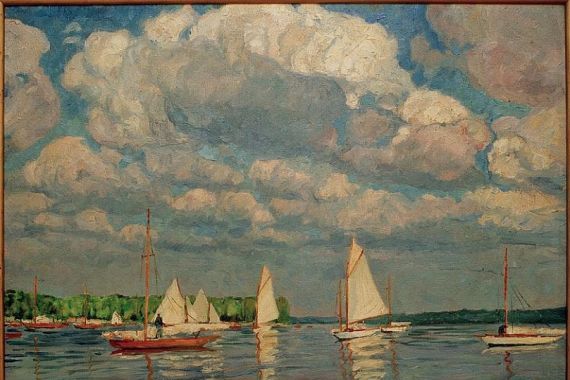

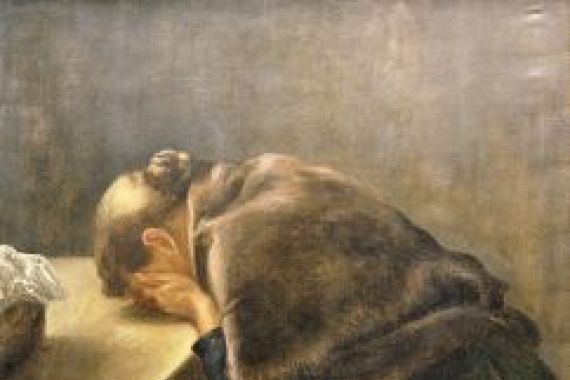

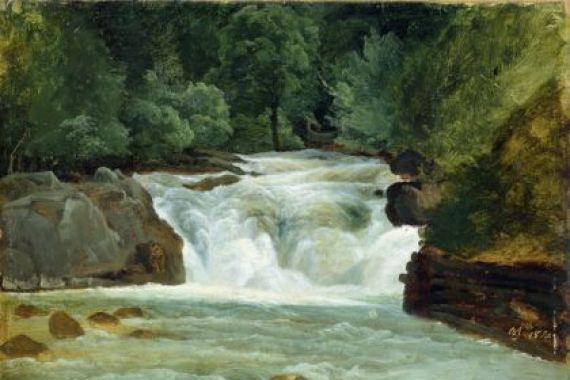

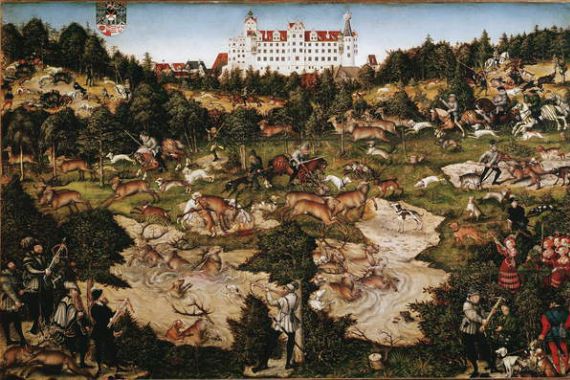

Anyone who claims that German art is merely a mirror of history underestimates its power: rather, it is a vibrating stream that absorbs the currents of the times, transforms them and hurls them back into the world with unexpected force. In Germany, art is never mere decoration - it is a dialogue, often a debate, sometimes an outcry. The political upheavals, the intellectual revolutions, the longing for identity and the desire to experiment - all this has been reflected in the studios, on the canvases and in the sketchbooks. When you look at a German watercolour, you not only see colour on paper, but also sense the struggle for expression, the search for truth, the play with light and shadow that has driven artists over the centuries.

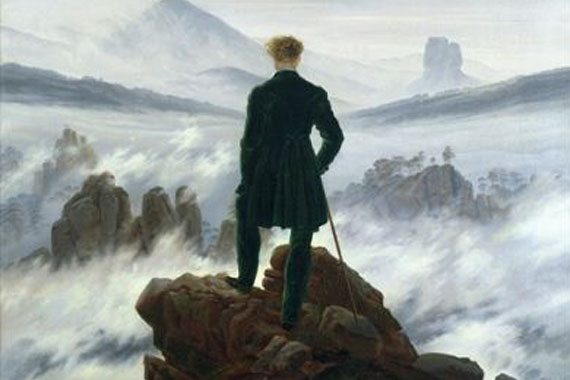

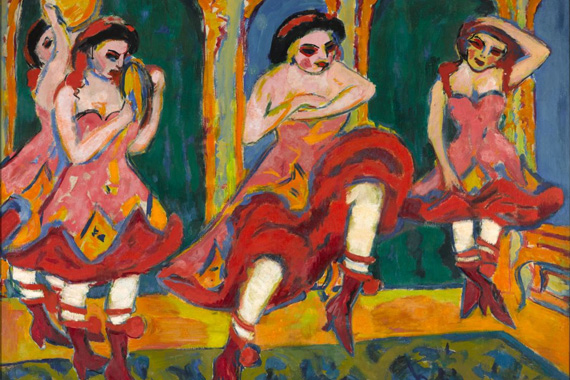

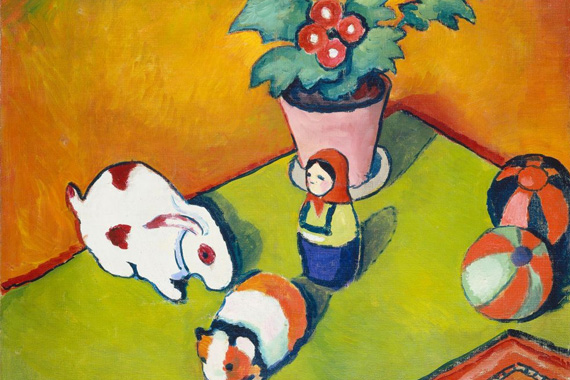

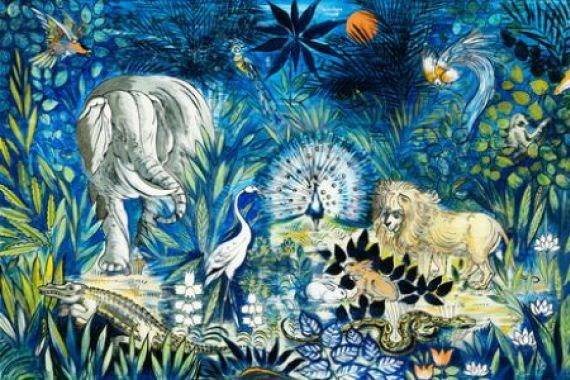

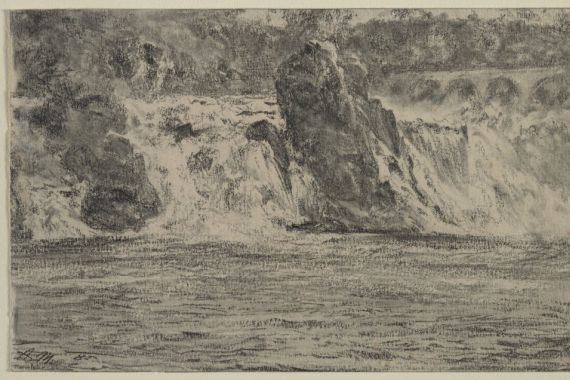

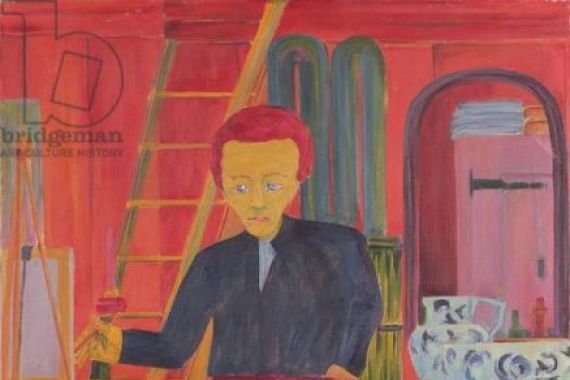

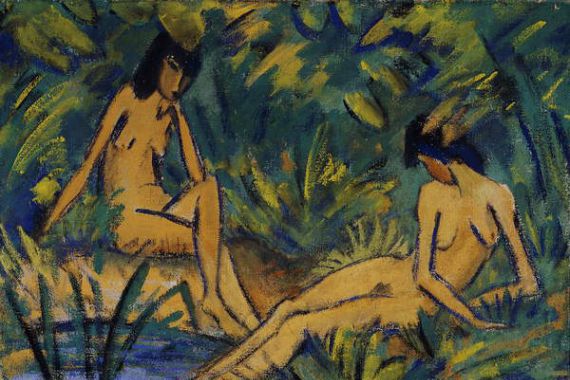

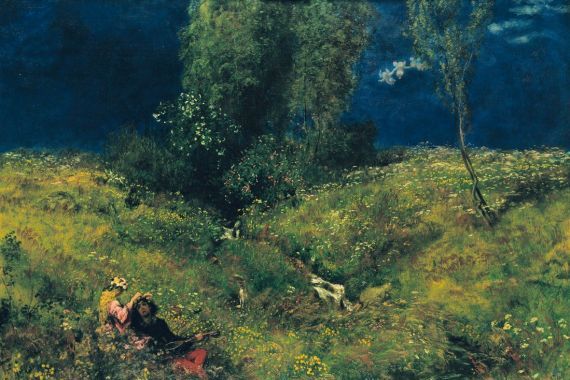

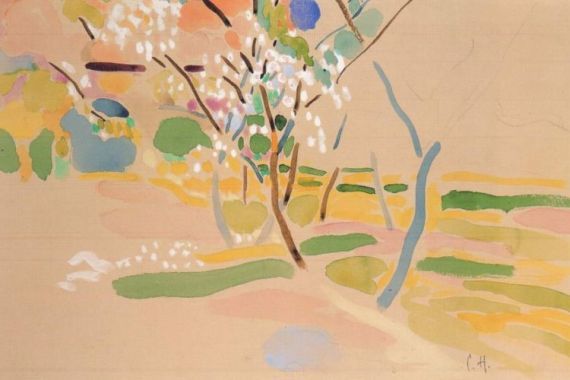

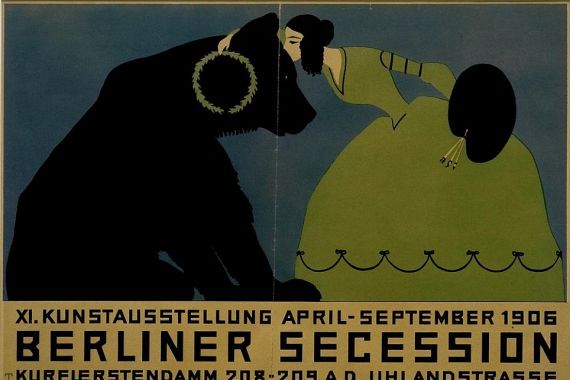

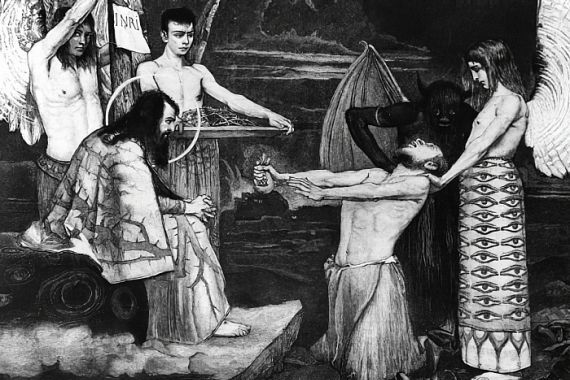

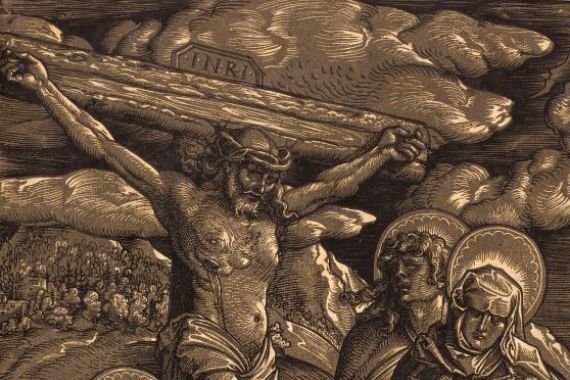

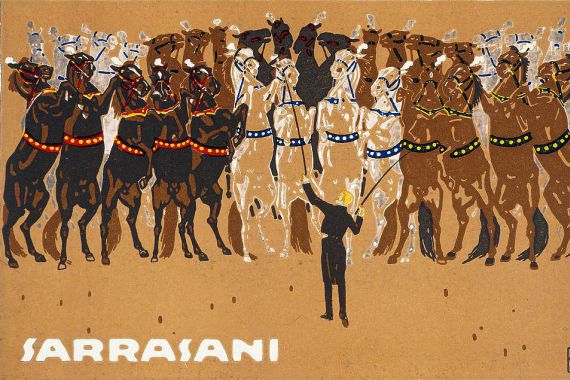

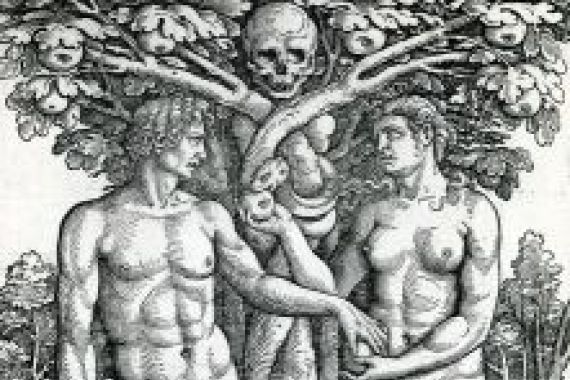

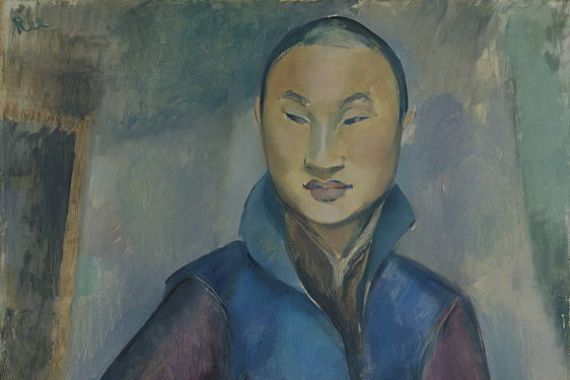

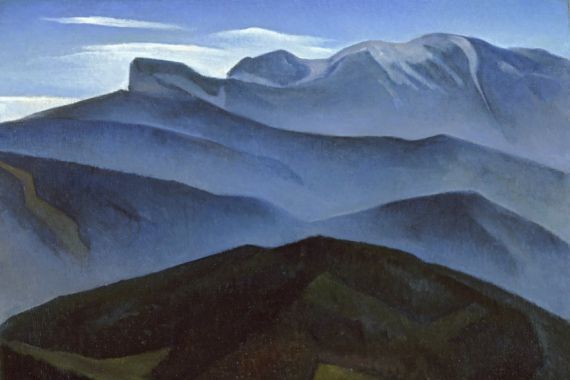

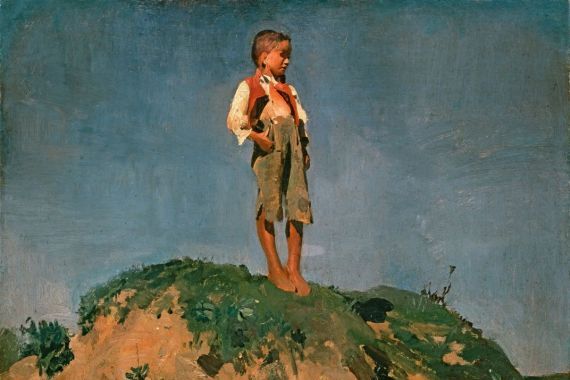

One look at Caspar David Friedrich's "Wanderer above the Sea of Fog" is enough to realise how closely interwoven art and zeitgeist are in Germany. Here, a man stands alone on a rock, with the endless, mysterious sea of fog in front of him - a symbol of the romantic longing for the infinite, but also of the feeling of being lost in a rapidly changing world. Friedrich's oil paintings are not mere landscapes, but landscapes of the soul, reflecting German Romanticism with all its melancholy and rebellion against the everyday. But German art does not stand still: With the advent of modernism, the colour palette exploded, the forms became more angular, the themes more political. The Brücke painters in Dresden, above all Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, hurled their colours onto the canvas like fanfares, as if they wanted to reinvent the world. Their woodcuts and gouaches are wild, raw, full of energy - a new departure that shakes up the European art scene.

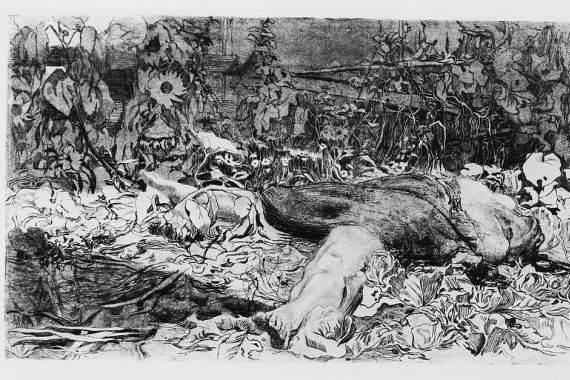

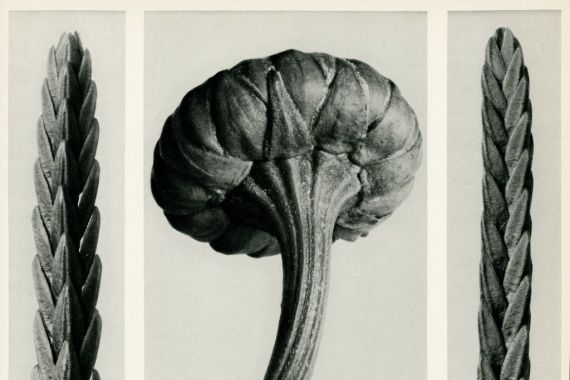

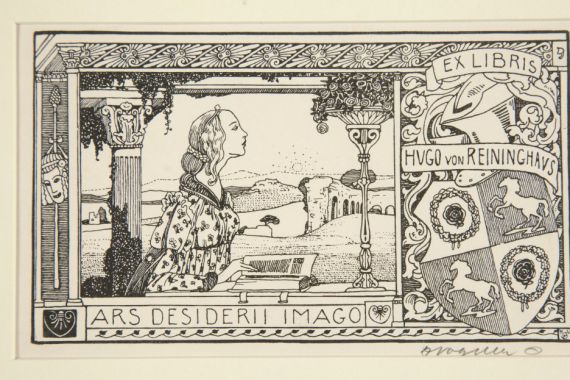

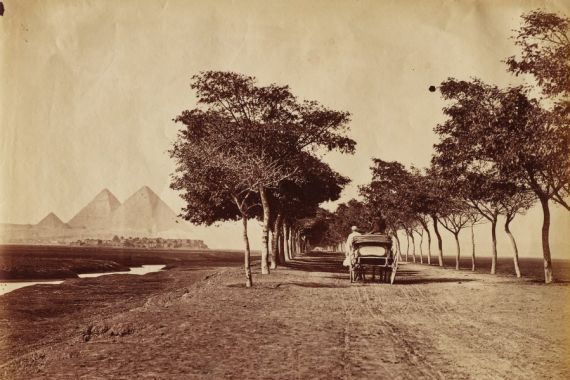

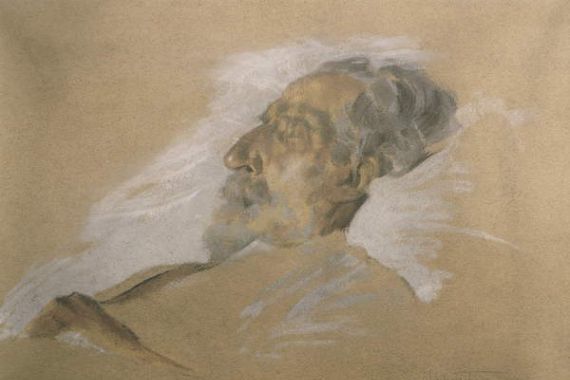

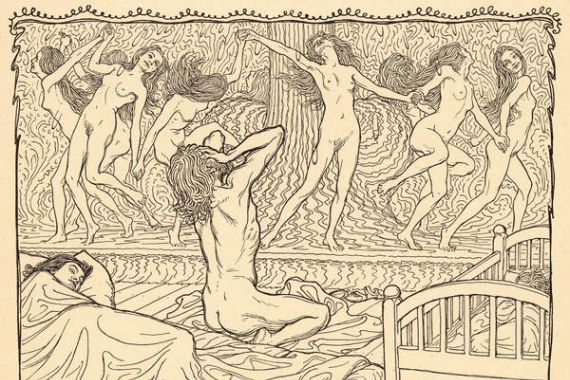

Photography and printmaking were elevated to independent arts in Germany long before they were recognised as such elsewhere. August Sander's portraits are more than illustrations - they are a panorama of German society, a quiet but powerful testimony to dignity and change. The Bauhaus photographers experimented with light, perspective and abstraction, as if they wanted to dissect the world into its individual parts and reassemble it. And while the Nazis were trying to gag art, works of breathtaking power were being created in secret: Otto Dix's etchings, for example, which captured the horror of war with unsparing precision, or Hannah Höch's collages, which used scissors and glue to push the boundaries of what could be said. Finally, after the war, German art became a laboratory of freedom - from the expressive colour fields of Gerhard Richter to the conceptual photographic works of Hilla Becher. Again and again, German art reinvents itself, remains uncomfortable, remains awake. Anyone who engages with it discovers not only pictures, but entire worlds - and perhaps also a piece of themselves.

Anyone who claims that German art is merely a mirror of history underestimates its power: rather, it is a vibrating stream that absorbs the currents of the times, transforms them and hurls them back into the world with unexpected force. In Germany, art is never mere decoration - it is a dialogue, often a debate, sometimes an outcry. The political upheavals, the intellectual revolutions, the longing for identity and the desire to experiment - all this has been reflected in the studios, on the canvases and in the sketchbooks. When you look at a German watercolour, you not only see colour on paper, but also sense the struggle for expression, the search for truth, the play with light and shadow that has driven artists over the centuries.

One look at Caspar David Friedrich's "Wanderer above the Sea of Fog" is enough to realise how closely interwoven art and zeitgeist are in Germany. Here, a man stands alone on a rock, with the endless, mysterious sea of fog in front of him - a symbol of the romantic longing for the infinite, but also of the feeling of being lost in a rapidly changing world. Friedrich's oil paintings are not mere landscapes, but landscapes of the soul, reflecting German Romanticism with all its melancholy and rebellion against the everyday. But German art does not stand still: With the advent of modernism, the colour palette exploded, the forms became more angular, the themes more political. The Brücke painters in Dresden, above all Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, hurled their colours onto the canvas like fanfares, as if they wanted to reinvent the world. Their woodcuts and gouaches are wild, raw, full of energy - a new departure that shakes up the European art scene.

Photography and printmaking were elevated to independent arts in Germany long before they were recognised as such elsewhere. August Sander's portraits are more than illustrations - they are a panorama of German society, a quiet but powerful testimony to dignity and change. The Bauhaus photographers experimented with light, perspective and abstraction, as if they wanted to dissect the world into its individual parts and reassemble it. And while the Nazis were trying to gag art, works of breathtaking power were being created in secret: Otto Dix's etchings, for example, which captured the horror of war with unsparing precision, or Hannah Höch's collages, which used scissors and glue to push the boundaries of what could be said. Finally, after the war, German art became a laboratory of freedom - from the expressive colour fields of Gerhard Richter to the conceptual photographic works of Hilla Becher. Again and again, German art reinvents itself, remains uncomfortable, remains awake. Anyone who engages with it discovers not only pictures, but entire worlds - and perhaps also a piece of themselves.

×